Introduction

Writing systems

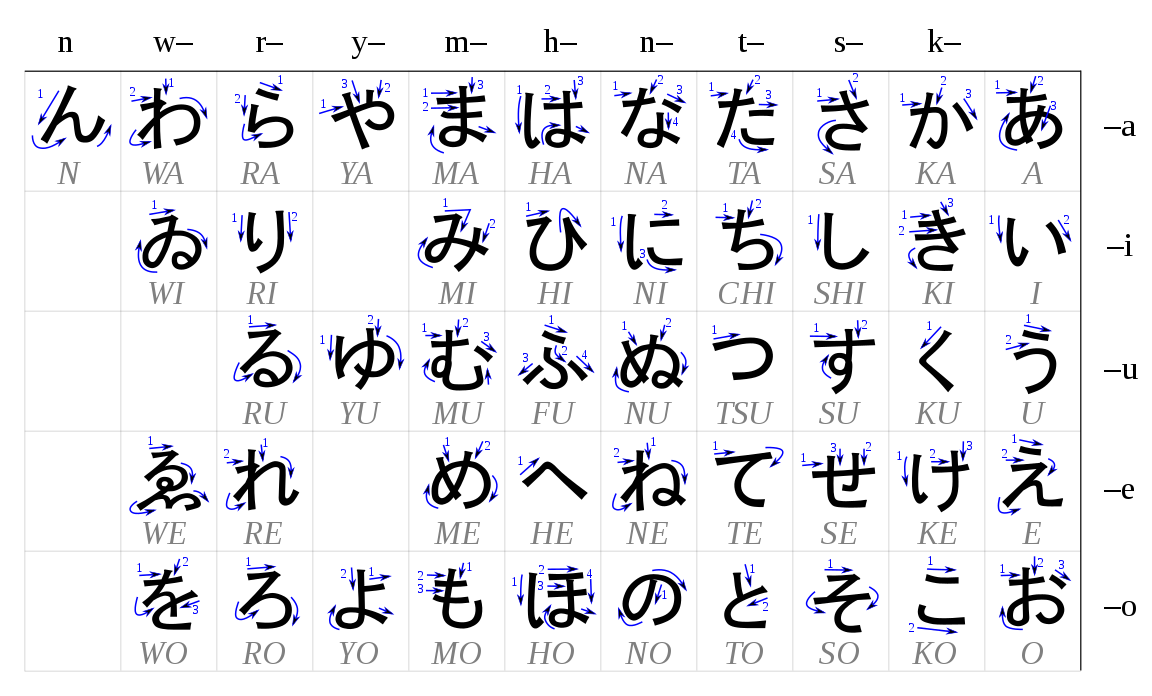

- The japanese writing systems is made with 3 kind of characters: Kanji, Hiragana and Katakana.Hiragana and Katakana represent sound, so they are always pronounced the same way, but there are used differently.

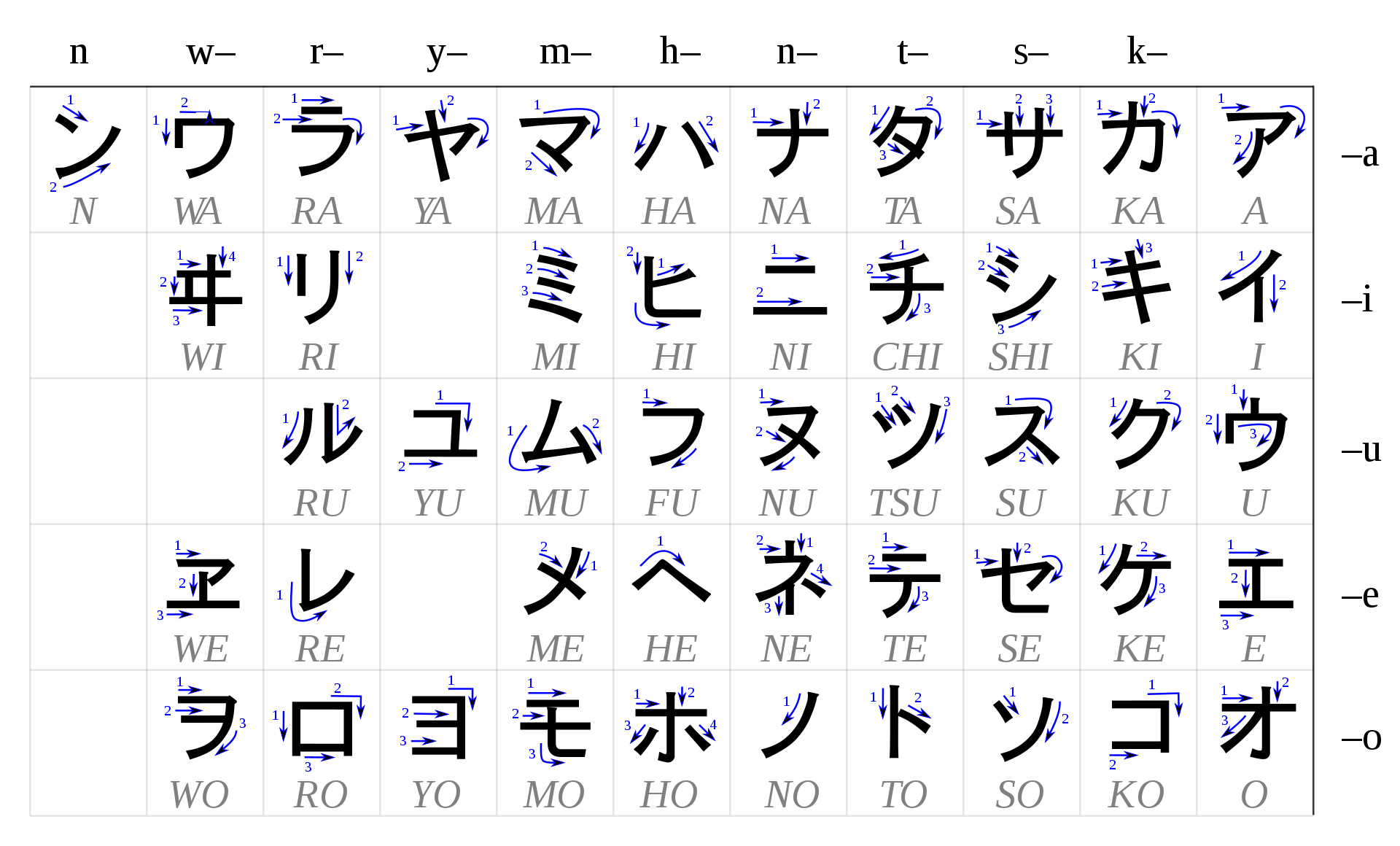

Katakana is used for foreign words (テレビ: "Terebi" = TV) so it's less frequent.

Here's an example:

アメリカ 人 です。

America - person - "is".

Pronouns can be omitted in japanese. like in this example. So this sentence could mean "I am american" or "He/She is american".

アメリカ (A-Me-Ri-Ka) is written in Katakana, like most foreign words.

人 (Jin) is a Kanji. It means person.

です (~ is) is written in Hiragana.

Hiragana

For the sake of simplification, consider that everything can be written in hiragana.Hiragana Chart :

Katakana

Katakana is used mostly for foreign words or onomatopoeia.It's the same sounds as hiraganas but written differently.

It's more rigid in appearance.

Like so : ひらがな (Hi Ra Ga Na) - カタカナ (Ka Ta Ka Na)

Katakana Chart:

Kanjis

Kanjis are characters borrowed from chinese.They can represent an idea/concept, a sound or both.

They can be read in different very ways.

私 can be read わたし (watashi) or あたし (atashi).

You can think about them like emoticons :

I ❤️ japanese from the bottom of my ❤️.

❤️ is written the same but have different readings (love and heart in this eemple).

The reading are divided in two categories :

- on'yomi (from Chinese)

- kun'yomi (native Japanese)

Some kanjis can have a lot of different readings. That's why it's often recommended in your studies to only focus on the concept/meaning. and learn readings in the context of vocabulary.

However, there are a lot of different opinions on what is the "best way" to study kanjis.

Kanjis are made of small parts called radicals.

明 : bright (日: sun + 月: moon)

Those radicals can be Kanjis themselves.

- 山 (mountain)

- 木 (tree)

- 火 (fire)

There are a lot more to the study of kanjis. but this deck focus on grammar.

Furigana

We saw that Kanji have different readings.To help knowing how to read the kanji, there can be the reading written above the Kanji.

It's written in hiragana and is called furigana.

Furigana are always included in this deck.

Rōmaji

Rōmaji is a way to write japanese sound in english alphabet.It exists so you can pronounce japanese without being able to read it.

Example : ありがと (japanese) = arigato (rōmaji).

Translations

The translations are here to help you understand the sentence.Don't learn them or rely on them too much.

Keep in mind that Japanese and English are two very different languages that work differently.

Some concepts don't translate well, because they don't have a counter part.

It can even be counter productive to find an english equivalent.

The idea is to understand japanese. not translate it in an other language.

Politeness

The Japanese language possesses a speech-level hierarchy that determines how one should address any given person based on various factors: relationship, age, role, respect, etc.Typically, Japanese learners are first introduced to polite speech. This is because polite speech is what is used in most daily interactions.

However, the greatest flaw made by introducing polite speech first lies in the fact that it is not the base form of speech.

Politeness is an auxiliary element to conversation. The purpose is not to provide information other than social implications.

Grammatically, plain speech is what makes up the base form of the language.

It's the basis for conjugation, to which politeness is then added.

As a rule of thumb, the longer the word (with a prefix like お) or the sentence, the more respectful it is.

Polite suffix

Japanese use differents honorifics, usually attached to the name.Sama

The most formal honorific suffix is -sama, and it’s used for God (kami-sama) and royalty (ohime-sama).

San

The most common formal honorific is -san, it translates (approimately) to Ms. and Mr. .

Chan

This is an endearing female honorific. While it’s most commonly used for children, it’s also used fairly widely among family and friends.

Kun

This is the male equivalent of –chan, it’s used for kids and between peers and friends.

You'll also find the prefix お (O) and ご (Go) beforn noun to make it sound more polite.

Omission

In japanese, you can convey a lot of information with a few words.Context, or social awareness plays a massive part in understanding the language.

Pronouns are usually omitted in japanese, implied by context.

Gender and plural

There is no gender and plural in japanese.It is understood by context.

In short sentences given as examples, more than one translation are possible.

学生 can mean student or students, and the student(s) can be a boy or girl.

Pronouns

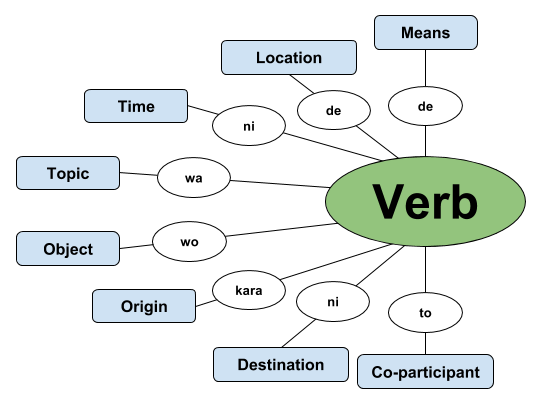

Japanese usually avoid pronouns and use the person's name instead.Sentence Structure

In Japanese, word order is more flexible than in English.Information is structured around particles.

Particles, not word order, are what determines how each part of a sentence relates to the verb.

They are placed after the word they are attached to.

A usual japanese sentence names a subject, objects marked by particles and ends with the verb.

There are usually ending particles after the verb that give a general tone to the sentence.

https://8020japanese.com

Basic Sentence

だ - Is

だ is a copula.It's not the verb "to be" but it can be translated as "is".

It is used to declare what one believes to be a fact.

だ can be omitted, but it's very casual.

⚠ No だ and だ's conjugations after い-Adjectives.

Both だ and い-Adjectives express a state of being, one following the other would be a redundancy and grammaticaly incorrect.

私だ。 It’s me. (casual)

本だ。 It’s a book. (casual)

猫だ。 (It) is a cat. (casual)

|

蛙だ |

|---|---|

| It's a frog. | |

|

海だ |

| It's the ocean! | |

|

飴だ |

| Candy... | |

です - Is (polite)

です is a copula.It indicates politeness and always goes at the end of a sentence.

In english both だ and です can be translated by the verb "To be", which leads to confusion.

です is used in polite sentences and can be seen as the polite form of だ, but it's not.

They are not the same, They are used differently grammaticaly.

Because です indicates politeness, you can use it after い-Adjectives whithout redundancy, You can't with だ.

トムです。 I am / It is Tom. (polite)

お 母さんです。 She is (my/her/his) mom. (polite)

レストランです。 It is a restaurant. (polite)

|

畑です |

|---|---|

| It's a farm. | |

|

好きです |

| I like you. | |

|

笹子です |

| It's me, Sasako! | |

は - Topic particle

は is a particle that indicates the topic of the sentence."A は B だ" is the most basic sentence structure.

It means A is B.

は is pronounced わ, The prononciation changed over the years but the spelling as は stayed.

トムは 先生だ。 Tom (as the topic of this sentence) is a teacher.

私はトムです。 I am / It is Tom. (polite)

明日は 月曜日だ。 Tomorrow (as the topic of this sentence) is Monday.

|

私はイクラ |

|---|---|

| I have salmon roe. | |

|

俺は 本物だ |

| I'm the real deal! | |

|

私は 神です |

| I'm a god. | |

じゃない - Is not

To turn a positive sentence into a negative one, you can replace the copula だ by じゃない."A は B じゃない" means A is not B.

The full form is : ではない, but では can be abbreviated to じゃ.

There can be many combinations with various degrees of politeness :

ではありません

じゃありません

ではないです

じゃないです

じゃん

⚠ No だ and だ's conjugations after い-Adjectives.

Both だ and い-Adjectives express a state of being, one following the other would be a redundancy and grammaticaly incorrect.

犬じゃない。 (It) is not a dog.

先生じゃない。 (I) am not a teacher.

一人じゃない。 You are not alone.

|

私は 敵じゃないわ。 |

|---|---|

| I'm not your enemy. | |

|

お 勉強じゃない |

| That's not homework. | |

|

人間は 仲間じゃない |

| Humans are not comrades. | |

ではありません - Is not (polite)

You can replace the copula です by ではありません to make the sentence negative.では can be abbreviated by じゃ.

There can be many combinations with various degrees of politeness.

From polite to casual:

ではありません

じゃありません

ではないです

じゃないです

私は 中学生ではないです。 I am not a junior high student.

彼女はお 医者さんではないです。 She is not a doctor.

彼は 高校生ではありません。 He is not a high school student.

|

落語ではありません |

|---|---|

| It's not traditional story telling. | |

|

伴 音ではありません |

| I am not Tomone. | |

|

そういう 問題ではありません |

| That isn't the issue here. | |

か - Question particle

Add か at the end of a declarative sentence to turn it into a question.Unlike English, word order does not change in Japanese when changing a sentence into a question.

The sentence has to go up in pitch (upward intonation) to indicate a question.

か is like an oral "?".

か is usually used with a period : か。

For casual questions, か can be replaced by the other particle の or just omitted.

お 元気ですか。 Are you fine? (How are you?)

お 名前は 何ですか。 What is your name ?

いくらですか。 How much is it ?

|

僕ですか |

|---|---|

| Me? | |

|

陽平 君は 元気ですか |

| Is Youhei-kun well? | |

|

はい! こうですか? |

| Right! Like this? | |

Adjectives

い-Adjectives

There are two type of adjectives, い-Adjectives and な-Adjectives.い-Adjectives are called that way because they always end in い.

い-Adjectives behave like verbs and can be conjugated.

Therefore, they can be placed at the end of a sentence.

You don't need to add a verb or a copula to make a correct sentence.

Because い-Adjectives already behave like verbs, you cannot add だ or one of his conjugation after it.

It would be redundant.

You conjugate the い-Adjective directly.

However, you can add です for politeness.

今日は 暑い。 It is hot today.

面白い 映画。 An interesting movie.

高いです。 That is expensive.

|

すごい! |

|---|---|

| Incredible! | |

|

あ~ 暑い! |

| Man, it's hot! | |

|

大きい…。 |

| It's huge... | |

な-Adjectives

There are two type of adjectives, い-Adjectives and な-Adjectives.They are called な-Adjectives beacuse you attach な to the adjective before a noun.

Few な-Adjectives can also end in い (like 綺麗 : きれい, pretty), but い-Adjectives all end in い.

Conjugating な-Adjectives is the same as conjugating nouns.

By conjugating the copula, That's why you can place the copula だ after a な-Adjectives.

暇な一 日。 A free day. (A a day with nothing to do)

私は 暇だ。 I am free. (I am bored or I have nothing to do)

彼は 静かだ。 He is quiet.

|

静かだ |

|---|---|

| It's quiet. | |

|

元気だよ。 |

| Yeah, I'm okay. | |

|

上手だ。 |

| Very nice. | |

Conjugation - Copulas

だった - Past

You can conjugate the copula だ.The positive past form is: だった.

It can be translated as "was" or "were".

⚠ No だ and だ's conjugations after い-Adjectives.

Both だ and い-Adjectives express a state of being, one following the other would be a redundancy and grammaticaly incorrect.

トムだった。 It was Tom.

大変だった。 (It) was terrible.

便利だった。 (It) was convenient.

|

元気だった? |

|---|---|

| How've you been? | |

|

ダメだったの |

| It didn't work? | |

|

大変だったわね |

| It must've been tough outside, right? | |

でした - Past (polite)

You can conjugate the copula です.The positive past form is: でした.

It can be translated as "was" or "were".

ラッキーでした! I was lucky!

犬でした。 It was a dog.

猫でした。 It was a cat.

|

大変でしたね |

|---|---|

| That must have been rough. | |

|

いいお 湯でした |

| That was a great bath... | |

|

残念でした |

| Nice try. | |

じゃなかった - Past negative

You can conjugate the copula だ.The negative past form: ではなかった or じゃなかった.

It can be translated as "was not" or "were not".

⚠ No だ and だ's conjugations after い-Adjectives.

Both だ and い-Adjectives express a state of being, one following the other would be a redundancy and grammaticaly incorrect.

りんごじゃなかった。 (It) was not an apple.

簡単じゃなかった。 That wasn't easy.

昨日は、 日曜日ではなかった。 Yesterday was not Sunday.

|

夢じゃなかった |

|---|---|

| It wasn't just a dream. | |

|

夢 じゃ なかっ た |

| It wasn't a dream? | |

|

えっ 天竜寺じゃなかった? |

| Oh, it wasn't Tenryuuji? | |

ではありませんでした - Past negative (polite)

You can conjugate the copula です.The negative past form: ではありませんでした.

It can be translated as "was not" or "were not".

コーヒーではありませんでした。 It wasn't coffee.

私は 昨日、 暇ではありませんでした。 I didn't have free time yesterday.

チキンではありませんでした。 That wasn't chicken

|

わたくしも 嫌いではありませんでした |

|---|---|

| I must admit, I'll miss it here. | |

Pronoun

何 (なに) - What

何 (なに) means what.When used as a prefix, the reading changes to なん.

It's followed by a counter, like 時 (time). 何時 means what time.

何 or 何だ can also be used as interjection meaning "what!".

何で means "why ? or how ?".

なに! What ! (Interjection)

何 時ですか。 What time is it ?

何ですか。 What is that?

|

何? |

|---|---|

| What? | |

|

何ですか。 |

| What is that? | |

|

えっと 何 時だ? |

| What time is it? | |

これ - This

Demonstratives indicate which entities are being referred to.They follow the same pattern of こ そ あ, ordered by proximity.

これ : This, Close to the speaker.

それ : That, Close to the listener.

あれ : That, Far from speaker and listener.

This pattern is sometimes called Kosoado (こ そ あ ど).

これは 何ですか? What is this?

これは 本です。 This is a book.

これは 犬だ。 This is a dog.

|

こ これは 何ですか? |

|---|---|

| Wh-What is this? | |

|

何 これ |

| What is this? | |

|

これ? |

| This? | |

それ - That

Demonstratives indicate which entities are being referred to.They follow the same pattern of こ そ あ, ordered by proximity.

これ : This, Close to the speaker.

それ : That, Close to the listener.

あれ : That, Far from speaker and listener.

This pattern is sometimes called Kosoado (こ そ あ ど).

それは 本です。 That is a book. (near listener)

それは、ギターです。 That is a guitar. (near listener)

それはケーキです。 That is a cake. (near listener)

|

それ 何 |

|---|---|

| What's that? | |

|

それは 弁当 |

| That's a boxed lunch (bento). | |

|

それは 魚! |

| That's a fish (sakana)! | |

あれ - That over there

Demonstratives indicate which entities are being referred to.They follow the same pattern of こ そ あ, ordered by proximity.

これ : This, Close to the speaker.

それ : That, Close to the listener.

あれ : That, Far from speaker and listener.

This pattern is sometimes called Kosoado (こ そ あ ど).

あれは 何? What is that (over there)?

あれは 電車です。 That (over there) is a train.

あれは 朝ごはん。 That (over there) is breakfast.

|

あれは? |

|---|---|

| What was that? | |

|

あれは どんな 本? |

| What's that book like? | |

|

あれは 何 |

| What was that? | |

この - This (+ noun)

When これ それ あれ are followed by a noun, we replace the れ by の.They follow the same pattern of こ そ あ, ordered by proximity.

The difference between これ and この is that この directly describes what comes directly after it.

この その あの must be followed by a noun.

この : This, Close to the speaker.

その : That, Close to the listener.

あの : That, Far from speaker and listener.

This pattern is sometimes called Kosoado (こ そ あ ど).

この 飲み物は 何ですか? What is this drink?

この 動物は 猫です。 This animal is a cat.

この 時計は 高いですか。 Is this watch expensive?

|

この 縄 |

|---|---|

| This rope... | |

|

この 人 |

| This guy. | |

|

何 この 会話 |

| What is this conversation? | |

その - That (+ noun)

When これ それ あれ are followed by a noun, we replace the れ by の.They follow the same pattern of こ そ あ, ordered by proximity.

The difference between これ and この is that この directly describes what comes directly after it.

この その あの must be followed by a noun.

この : This, Close to the speaker.

その : That, Close to the listener.

あの : That, Far from speaker and listener.

This pattern is sometimes called Kosoado (こ そ あ ど).

その 動物はサルです。 That animal is a monkey. (near listener/previously mentioned)

そのバスは 速い。 That bus is fast. (near listener/previously mentioned)

その 仕事は 難しいです。 That job is difficult. (near listener/previously mentioned)

|

そのブラシ |

|---|---|

| That brush... | |

|

その 声は… |

| That voice... | |

|

その 荷物… |

| What's with those bags? | |

あの - That over there (+ noun)

When これ それ あれ are followed by a noun, we replace the れ by の.They follow the same pattern of こ そ あ, ordered by proximity.

The difference between これ and この is that この directly describes what comes directly after it.

この その あの must be followed by a noun.

この : This, Close to the speaker.

その : That, Close to the listener.

あの : That, Far from speaker and listener.

This pattern is sometimes called Kosoado (こ そ あ ど).

あの is also an interjection, when you're unsure about what to say (well; um; er..)

あの 人はトムです。 That person is Tom.

あの ラーメン屋は 美味しいです。 That ramen shop is delicious.

あの 日は 雨だった。 That day (long ago) was rainy.

|

あの 車… |

|---|---|

| That car... | |

|

あのバカ… |

| That idiot… | |

|

あの 林も? そう |

| Those trees? -Yes. | |

ここ - Here

We follow the usual pattern of こ そ あ, for locations as well.ここ そこ あそこ are used to refer to a place.

ここ : Here, Close to the speaker.

そこ : There, Close to the listener.

あそこ : Over there, Far from speaker and listener.

ここです。 (It’s) here.

ここは、 台所。 Here is the kitchen.

ここは 遊ぶところじゃない。 This isn't a place to play.

|

ここだ |

|---|---|

| In here. | |

|

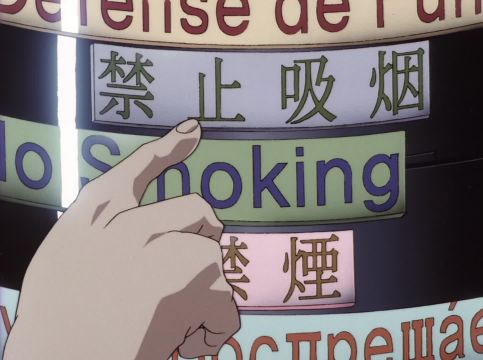

ここは 禁煙だ |

| ...no smoking in here. | |

|

ここいいー |

| This is nice. | |

そこ - There

We follow the usual pattern of こ そ あ, for locations as well.ここ そこ あそこ are used to refer to a place.

ここ : Here, Close to the speaker.

そこ : There, Close to the listener.

あそこ : Over there, Far from speaker and listener.

そこ。 There. (previously mentioned or near listener)

たぶん、そこ。 There. probably. (That place)

そこは、トイレです。 That place is the bathroom (toilet). (near listener)

|

そこだ |

|---|---|

| Look at that. | |

|

ほら そこだよ |

| See? There's the dock. | |

|

そこは 暖かく |

| It's warm | |

あそこ - Over there

We follow the usual pattern of こ そ あ, for locations as well.ここ そこ あそこ are used to refer to a place.

ここ : Here, Close to the speaker.

そこ : There, Close to the listener.

あそこ : Over there, Far from speaker and listener.

あそこは 静か。 It is quiet over there.

ほら あそこ。 Look there.

あそこは 寒い。 It's cold over there.

|

あそこだ |

|---|---|

| Over there. | |

|

砂糖は あそこだ |

| The sugar's over there. | |

|

ほら あそこ |

| Look there. | |

Conjugation - Present

Stem form

There are る-verbs (Ichidan - group 1) and う-verbs (Godan - group 2).The last hiragana of the verb indicates the group.

る verbs always end in る.

う verbs end in various hiragana, and sometimes end in る as well.

The verb without the last hiragana is called the "stem form".

It's upon that stem form that all conjugations are built.

Verbs are by default presented in what is called the Dictionary or plain-form.

It's called that way because that's how you will find a verb in a Dictionary.

Non Past - Postive Form

The present tense is used to describe something habitual or frequent.It can also represent something you'll be doing in the future.

Because it can describe actions for both present and future, it is sometime called "non past form" as it's more accurate than just present.

Non Past - Negative Form

Ichidan : take off る and add ない (casual).Godan : replace the last う sound with the matching あ sound, Add ない.

Godan : for verbs that end in う, it becomes わ rather than あ.

Non Past - Polite form

All polite verbs end with ます.It's the more polite version of the Dictionary / plain form.

Most textbooks will introduce the polite form has the conjugation "by default", It's because you're expected to speak in formal way before a casual way.

However remember that the polite form is a conjugation form.

Particles

は - Topic particle

は is a particle that indicates the topic of the sentence.But by omitting the rest of sentence, は can be used to ask question, usually about some information shared by the questioner and listener.

晩ご飯は? How about dinner ?

トムさんは。 What about Tom ?

私はジョンです。 I am John.

|

ここは? |

|---|---|

| How about here? | |

|

名前は? |

| Name? | |

|

ご 飯は? |

| What about food? | |

か - Or; whether or not

A particle which marks an alternative, a choice between two things (or more) like “or.”ここかそこ。 Here or there?

コーヒーかお 茶。 Coffee or tea.

今日か 明日。 Today or tomorrow.

|

門か 森か |

|---|---|

| The gate, or the forest? | |

|

答えはイエスかノー |

| The answer is yes or no. | |

|

笹か 竹ください |

| Could I get bamboo or bamboo grass, please? | |

を - Indicates direct object of action

を is used to show the direct object of a sentence.Direct objects receive the action of the verb.

を is pronounced like お.

何を 飲みますか。 What will you drink?

何を 食べますか。 What will you eat?

テレビを 見ます。 I watch TV.

|

何を 作った |

|---|---|

| What did you make?! | |

|

娘を 捕らえろ |

| Get the girl. | |

|

何をする |

| What are you doing? | |

へ - To (direction, state); toward; into

へ and に are both used with locations.They are almost interchangeable.

へ emphasizes the direction of the location, It focuses on the journey.

に emphasizes a specific location, It focuses on the destination.

へ can be translated by "to" or "toward".

学校へ 行きます。 I'll go to school.

どこへ? Where to?

うちへかえります。 I'll return home.

|

みんな! 城へ~! |

|---|---|

| Everyone to the castle! | |

|

南極へ 行く! |

| Is going to Antarctica! | |

|

学校へ |

| ...go to school. | |

に - Direction (To; toward.)

へ and に are both used with locations.They are almost interchangeable.

へ emphasizes the direction of the location, It focuses on the journey.

に emphasizes a specific location, It focuses on the destination.

へ can be translated by "to" or "toward".

学校に 行きます。 I'll go to school.

病院に 行く。 To go to the hospital.

うちにかえります。 I'll return home.

|

家に… |

|---|---|

| To my house... | |

|

君は 家に 戻れ |

| Go back home. | |

|

海に 行きます! |

| We're going to the ocean! | |

に - Place (In; at; on)

The particle に denotes the location where someone or something exists.東京に 住む。 I will live in Tokyo.

日本にいる。 I’m in Japan.

田中さんは、 公園にいる。 Tanaka-san is in the park.

|

じゃあ 一番上に |

|---|---|

| Well then, let's put it at the very top. | |

|

昔々 ある 所に |

| Once upon a time. In a certain land. | |

|

なんで 海にいるの? |

| Why is she at the ocean? | |

に - Target

に indicate targets (indirect objects).This is mostly used when you give or do something for someone.

私は 母に 手紙を 書きます。 I write letters to my mother.

私は 弟に 数学を 教えます。 I (will) teach mathematics to my younger brother.

お 父さんにプレゼントを 買います。 I (will) buy a present for father.

|

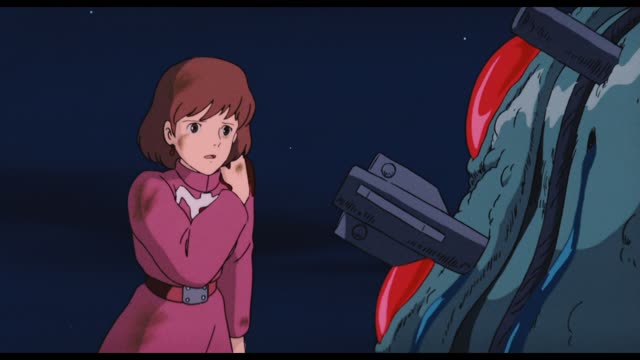

アシタカが 私に? |

|---|---|

| From Ashitaka? For me? | |

|

あたしに |

| For me? | |

|

みんなに 報告がある |

| I have some news for you all | |

に - Frequency

に follows the frequency of events over a period of time.Used as "per".

彼女は 一週間に 4 回ジムに 行きます。 She goes to the gym 4 times a week.

一週間に 3 回 働きます。 I work 3 times a week.

私は 一ヶ月に 一回 映画館 行きます。 I go to the movies once a month.

|

年に1 回のね |

|---|---|

| It's held once every year. | |

|

一週間に1 回くらい |

| About once a week. | |

|

120 年に一 度 羽化し |

| It hatches once every 120 years | |

に - Time

に follows the specific time you want to talk about, whether it's a date or an hour.Some time-expressions do not need に, like "today" or "tomorrow".

You also don't need に when you are describing regular intervals, like "every week".

金曜日に 行きます。 I will go on Friday.

10 時半に 戻ります。 I'll come back at 10:30.

明日 に来ます。 I will come tomorrow.

|

では 明日 7 時に |

|---|---|

| Then tomorrow at 7:00. | |

|

また 明日にする。 |

| I'll save it for tomorrow. | |

|

それは 金曜日に。 |

| Move the rest to Friday. | |

で - Range

で can express ranges, in time or space.There is a case that you don’t use the particle で even if you express a period of time,

If you express actions which take place for a while, the particle で is not generally used,

When you use the particle で, it indicates that you will complete actions,

Here are the comparisons :

1時間宿題をします。

do my homework for an hour,

1時間で宿題をします。

complete my homework within an hour.

パスポートは 六月で 切れる。 The passport expires in June.

私は1 時間で 会社に 着きます。 (I will) arrive at the office within an hour.

マンガは 世界で 有名だ。 Manga is famous in the world.

で - Means, method - by, with

で specifies the context in which the action is performed, the means, method or instruments.で follows the tool that you are using, The "tool" doesn't have to be a physical object.

It can be translated with : by, with, in, by means of …

飛行機で 帰る。 To go home by airplane.

私 達は 日本語で 話した。 We talked in Japanese.

ダンはリンゴでジュースを 作ります。 Dan will make juice by (using) apples.

|

これで 行くの? |

|---|---|

| We're going with this? | |

|

いや 名前くらいで |

| No, just by name. | |

|

なぜ 一人で? |

| Why'd you go alone? | |

で - Location of action (At; in; on)

で is used to indicate the location of an action.It can be translated with : at, in, on.

When you use an object to perform an action, で indicates what you are using.

で indicates that someone is doing something in a specific place.

そこで 何をしますか。 What will you do there (at that location).

私は 図書館で 本を 読みます。 (I will) read books at the library.

図書館で 日本語を 勉強します。 I study Japanese at the library.

|

僕 ここでいいよ |

|---|---|

| I'll be fine right here. | |

|

学校で |

| See you at school! | |

|

家で 寝たんだね |

| So he slept at home. | |

で - Amount

で can express amount,In this context, で can be placed after any word which indicates quantity.

私は100 万 円で 車を 買います。 (I will) buy the car for one million yen.

10 人でサッカーをします。 (I will) play soccer with ten people.

一人で 勉強します。 (I will) study alone.

も - Too; also; as well

も is a particle used to indicate that something that has previously been stated also holds true for the item currently under discussion.It corresponds with the English words "also" or "too", and replaces が, は or を when used.

Other particles, such as に, may be used in combination with も.

これも 古い。 This is also old.

これも 便利だ。 This is also convenient.

ノートも 必要。 A notebook is also necessary. (needed. required)

|

私も |

|---|---|

| Me too. | |

|

俺も 学校に 行く |

| I'm going to school, too. | |

|

私も 行こう |

| I'll join you too. | |

の - Possessive ( 's; of; in; at; for; by; from)

の is a particle that connects two nouns.The second noun is the main idea, the first is more specific.

It can be used to describe a possession: 私の本 (I の book = my book).

A and B in AのB relate to each other in various ways, and these relationships are determined by context.

A is the possessor of B.

A is the location where B exists.

B is about/on A.

A is a specific kind of B.

A is the object and B is the subject.

A created B.

...

これは 先生の 本だ This is my teacher's book.

私の 車はこの 車です。 My car is this car.

これは 映画の 雑誌です。 This is a movie magazine.

|

私の 名はアクア |

|---|---|

| My name is Aqua. | |

|

ここは 俺の 家だ! |

| This is my house. | |

|

これが 私の 家族 |

| This is my family. | |

の - Relative locations

Between two nouns, the first one indicates the nature or attribute of the second one with the help of の.This structure is used to describe locations.

You use the particle の between a reference and the relative location.

In english, it would be translated by "of", like "in front of", "left of"...

Relative locations :

前 (in front)

うしろ (behind)

中 (inside)

猫はテーブルの 上です。 The cat is on the table.

ペンは 机の 下です。 The pen is under the desk.

銀行は 図書館のとなりです。 The bank is next to the library.

|

木の 上 |

|---|---|

| On top of the tree... | |

|

この 下 なんか… |

| There's something under here. | |

|

席は 水 瀬の 隣だ |

| Your seat is next to Minase's. | |

が - Subject marker

A particle which indicates the subject.が and は seem similar when translated in english.

は focus on the subject / theme of the sentence.

が focus on the subject, it identifies something or someone specific.

あれが、いいです。 That (over there) is good.

川が、 細い。 The river is narrow. (subject)

木が、 高い。 The tree is tall. (subject)

|

私が |

|---|---|

| I did! | |

|

俺が |

| Me? | |

|

これが いい! |

| This is the one I want! | |

が - Describing

To describe people physical attributes, we use the particles は and が.トムさんは 髪が 長いです。 Tom has long hair.

トムさんは 頭がいいです。 Tom is bright.

トムさんは 背が 高くないです。 Tom is not tall.

と - With

と is used when you want to say things are being done with someone.It comes after a noun to mean "with noun".

家族と 散歩します。 I take a walk with my family.

先生と 食べます。 I will eat with the teacher.

あなたと 私です。 (It is) you and me.

|

ううん ママと |

|---|---|

| No, I'm with my mom. | |

|

もちろん 僕と |

| With me, of course. | |

|

付き合えよ 俺と |

| Go out with me. | |

だけ - Only; just; as much as~

だけ is a particle that is often equated with the english words “only” or “just”.However, だけ differs from these words in one important respect: it expresses a maximum, not a minimum, limit.

一人だけ。 One person only;

ほしいものはこれだけ。 This is the only thing I want.

いくら 何でも 15 人だけは 来るだろう。 Surely 15 people will come at least.

|

ちょっとだけね |

|---|---|

| I'll give you only a bit. | |

|

こいつは 口だけ |

| This one only knows how to bluff. | |

|

一本だけ |

| Just one. | |

Interogative pronouns

どれ - Which

The fourth element in the pattern こ そ あ ど is for questioning.どれ means "which ?".

どれがいいですか。 Which is good? (three or more objects)

どれを 選びますか。 Which will you choose? (three or more objects)

どれが 好ですか。 Which do you like? (three or more objects)

|

どれにしよう |

|---|---|

| I wonder what I should pick? | |

|

どれが 仙道だ |

| Which one of you is Sendo? | |

|

へえどれですか? |

| Which one? | |

どの - Which

The fourth element in the pattern こ そ あ ど is for questioning.どの means "Which ?" and must be followed by a noun.

は is not used with どの, We use が.

どの 寿司屋がいいですか。 Which sushi restaurant is good?

どのパソコンが 好ですか。 Which laptop do you like?

どの 項目をみますか? Which topic do you want to read?

|

どの 人? |

|---|---|

| Who? | |

|

どの 味にします |

| What flavor? | |

|

え? どの 絵が? |

| What? Which painting? | |

どこ - Where

The fourth element in the pattern こ そ あ ど is for questioning.どこ means "where?"

A common way to ask the location of X, is with this question:

X はどこですか。

どこに 行きますか。 Where are you going?

ここはどこ? Where is here? (What is this place?)

トイレはどこですか。 Where is the toilet?

|

ここはどこ? |

|---|---|

| Where are we? | |

|

ここどこ |

| Where am I? | |

|

それじゃどこに |

| So where are we going? | |

誰 (だれ) - Who

だれ means "Who?"Fomal form is どなた.

誰ですか。 Who is it?

誰がしますか。 Who will do it?

誰と 話ますか。 Who will you speak with?

|

誰 |

|---|---|

| Who's this? | |

|

誰 お 前 |

| Who are you? | |

|

誰なんだ お 前ら! |

| Who are you guys anyway? | |

Ending particles

な - Confirmation; admiration, etc

A sentence-ending particle that can used to express the following:- ask for confirmation from listener (…right?)

- express hope (it’d be nice if…)

- express admiration (wow…)

- express uncertainty (I wonder…)

- add general emphasis to what is being said

It can also be written as なあ.

There are some similarities with the other sentence ending particle ね (ne).

これ、 美味しいなあ。 This is really delicious.

頭が 痛いな。 I've got a headache...

すごいなあ! That's too awesome!

|

でかいな |

|---|---|

| He is really big... | |

|

いいな |

| How lucky... | |

|

おかしいなあ |

| That's strange. | |

わ - Weak emphatic particle

わ is a sentence-ending particle that indicates a slightly emphatic tone.It's mainly used by a female speakers.

わ precedes other sentence ending particles such as ね or よ.

今日は、さむいわ。 It's cold today.

今日は 暑いわ。 It's hot today!

そうですわね I agree.

|

きれいだわ。 |

|---|---|

| It's beautiful. | |

|

私は 敵じゃないわ。 |

| I'm not your enemy. | |

|

大変だわ! |

| This is terrible. | |

ね - Isn't it? Right? Eh?

Japanese has a few sentence ending particles to change the tone or feel of a sentence.ね is used when seeking confirmation or agreement, like "right ?" or "isn't it ?"

いい 質問ですね!︎ That is a good question. isn't it!︎

いいですね。 That’s good right?

昨日、 忙しかったね。︎ Yesterday was busy. wasn't it!︎

|

だいじょうぶかね? |

|---|---|

| Are you feeling all right? | |

|

すごいね |

| That is amazing. | |

|

まあね |

| I guess. | |

じゃん - Isn't it? Right? Eh?

This is the contracted form of じゃない, but it's used in a way to ask "isn't it ?".It can be used to confirm or to criticize something in an informal way.

いいじゃん。 That's good, isn't it!

(石田)くんじゃん Isn't that Ishida?

すごい じゃん。 How cool!

|

ダメじゃん! |

|---|---|

| No way! | |

|

立派じゃん え? |

| They're quite splendid. | |

|

うんいいじゃん |

| Excellent! | |

でしょう - I think; it seems; probably; right?

でしょう is used at the end of a sentence when you talk about a prediction, something uncertain, or to ask confirmation.It has an uncertain tone to it.

Can be translated by "right ?" or "probably".

The contracted form is でしょ.

でしょう is the polite form of だろう.

You can use でしょうか to ask another person's opinion or guess.

これは、いい 車でしょう。 This is a good car (probably).

明日は 雨が 降るでしょう。 It will probably rain tomorrow.

そうでしょう。 Possibly.

|

何でしょう |

|---|---|

| What is it? | |

|

涼しいでしょう |

| It's nice and cool, isn't it? | |

|

何者でしょう? |

| Who could have done this? | |

だろう - I think; it seems; probably; right?

Japanese has a few sentence ending particles to change the tone or feel of a sentence.だろう is used at the end of a sentence to ask confirmation.

Sometimes this grammar is shortened to just だろ, but the meaning is the same.

だろう is more masculine or casual version of でしょう.

Can be translated by "right ?" or "probably".

だろう is the volitional form of the copula である.

ここがいいだろう。 This is a good place. isn’t it? (Here is good. right?)

明日は 晴れるだろうか。 It'll probably clear up tomorrow.

ここは、 右だろう? It's a right here. isn't it?

|

どこだろう |

|---|---|

| I wonder where she is. | |

|

君は 誰だろう? |

| Who are you? | |

|

危ないだろう |

| It's not safe. | |

かしら - I wonder

Used in informal speech, almost exclusively by females, to express a high degree of uncertainty.The male version is かなあ which is used only in fairly informal situations.

どうしたのかしら みんな What are they doing?

こっちじゃないのかしら…。 Maybe she wasn't here.

え~っと これかしら Let's see... I wonder if this is it.

|

何かしら? |

|---|---|

| I wonder what it is... | |

|

そうかしら? |

| Oh, yeah? | |

|

どういう 意味かしら |

| I'm not sure what you mean. | |

かな - I wonder; should i?

かな (kana) basically means “I wonder”, and is mostly used to:- contemplate doing something

- wonder if something will happen

There are also many other subtle meanings which could be implied based on context, including:

- expressing doubt and asking advice

- expressing hope

- offering an opinion

- making a suggestion

- asking a small favor

- expressing desire or intention

外は 寒いかな。 I wonder if it’s cold outside.

トムかな? Is that Tom?

本当かな。 I wonder if it is true.

|

誰かな? |

|---|---|

| I wonder who it is. | |

|

休みかな |

| I wonder if they're closed. | |

|

唯 大丈夫かな? |

| I wonder if Yui's doing okay... | |

よ - You know; emphasis

よ indicates certainty or emphasis, like giving new information to the listener.バスで 帰りますよ。 I will return home by bus. (adds emphasis)

トムはあそこにいたよ。 Tom was over there. (adds emphasis)

飲み物を 買ったよ。 I bought drinks. (adds emphasis)

|

ここよ |

|---|---|

| Here we are. | |

|

すげぇよ! |

| That's amazing! | |

|

これが 友達だよ |

| And that is what friends are. | |

ぞ - I'm telling you; dammit

A sentence-final particle that strongly emphasizes a (usually male) speaker's emotion or conviction about something.It's like a stronger よ, that you will usually be used by strong men in anime or manga, as it's very informal.

よ~し 行くぞ! All right! Let’s go!

頑張るぞ。 I'm going to work hard!

とうとう 日本に 来たぞ。 We’re finally in Japan!

|

いくぞ~! |

|---|---|

| Let’s do it! | |

|

よし 行くぞ! |

| Okay! Let’s go! | |

|

ほら 牛乳だぞ |

| There, it's milk. | |

の - It is that ~

With rising intonation, it indicates a colloquial question like the particle か.It's the short form of んですか.

With falling intonation, it serves to soften the statement. Women and children usually employ this second usage.

今日、 何するの。 What are you going to do today?

学校に 行くの。 I'm going to go to school.

お 金が ないの。 See, I don’t have any money.

|

話すの? |

|---|---|

| You're still going to tell me? | |

|

どうしたの |

| What's the matter? | |

|

マジなの? |

| Are you serious? | |

Verbs

する - Do; make; play ...

する can be translated as "to do" but in a broader sense than in english.You can make a noun into a verb by adding する to it.

中山さんはテニスをします。 Mr. Nakayama plays tennis.

何をしますか。 What will you do? (polite)

私は 勉強をする。 I (do) study. (casual)

|

ペンギンさん、 何にする? |

|---|---|

| What would you like, Mr. Penguin? | |

|

さて 何するかな |

| Now, then. What should we play? | |

|

バカにするなよ |

| Hey, don't make fun of me. | |

来る - To come

来る (くる) is a word meaning "to approach the temporal or spatial location ".It is therefore, quite similar to the English verb "to come", however, there are some differences in usage.

来る can also be used to express the occurrence of natural phenomena, such as sunlight, wind, earthquakes or rain.

It can also be used to express that a condition (often something negative, such as illness, injury, etc.) has progressed or advanced to a certain specified state.

It's an irregular verb.

バスが 来る。 The bus is coming

彼女はいつ 来ますか。 When is she coming?

そろそろ 来ますか。 Will you be here soon?

|

来るな! |

|---|---|

| Stay back! | |

|

あ ( 夏目) 様 雨が 来ます |

| Natsume-sama, it's going to rain. | |

|

来るか! |

| Wanna fight? | |

ある - There is; is (non-living things)

The two verbs いる and ある are used to expressed existence and not actions.We can translate it by "there is …", but it refers to the existence and not a location.

You can use it to say someone or something is somewhere.

It can also be used when an event is being held, or having objects.

It's also used with abstact things, like experiences or time, opportunities...

ある is used for non-living things.

いる is used for living things (people, animals).

ある is used for plants.

The negative informal form of ある is not あらない but ない.

この 町には 大学が 三つあります。 In this town are three universities.

仕事がある。 There is work. (casual)

いい 質問がありますか。 Are there any good questions? (polite)

|

あるよ |

|---|---|

| There's one here. | |

|

お 願いがあります |

| I have a favor to ask! | |

|

問題ありません |

| It is not a problem. | |

いる - There is; to be; is (living things)

The two verbs いる and ある are used to expressed existence and not actions.We can translate it by "there is …", but it refers to the existence and not a location.

You can use it to say someone or something is somewhere.

It can also be used when an event is being held, or having objects.

It's also used with abstact things, like experiences or time, opportunities...

ある is used for non-living things.

いる is used for living things (people, animals, but not plants).

ある is used for plants.

この 町には 日本人が 沢山います。 In this town are many Japanese.

二人の 兄弟がいます。 There are two people. (Two people exist.)

田中さんとトムがいます Mr. Tanaka and Tom are there. (exist)

|

( 瀧)くんがいる |

|---|---|

| It's really you! | |

|

人がいる |

| There's a person. | |

|

おれもいる! |

| I'm here, too. | |

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Some verbs in japanese exist like pairs.Transitive verb : an action is done by someone, the verb has an object. We use the particle を.

Intransitive verb : something happens, the verb does not have an object. We use the particle が.

試合を 始めた・ 試合が 始まった I started the match. The match started.

忘れ物を 見つけた・ 忘れ物が 見つかった I found the lost item. The lost item was found.

虫を 集めた・ 虫が 集まった I gathered bugs. The bugs gathered.

Conjugation - Past

Past - Positive Form

IchidanTake off る and add た

Godan

Take off the last hiragana and replace it by ...

く → いた

ぐ → いだ

す → した

るうつ → った

む.ぶ.ぬ → んだ

Past - Negative Form

Take the Non-Past Negative form of a verb, It ends in ない.Take off the い and replace it with かった.

Past - Polite Form

い-Adjectives conjugation

Because い Adjectives behave like verbs, you can conjugate them.Behaving like verbs, they can end a sentence.

To turn い-Adjectives into the negative form, you change the い to くない.

⚠ No だ and だ's conjugations after い-Adjectives.

Both だ and い-Adjectives express a state of being, one following the other would be a redundancy and grammaticaly incorrect.

な-Adjectives conjugation

Conjugating な adjectives is the same as conjugating nouns.By conjugating the copula.

いい conjugation

The い-Adjective いい (good) is an exeption.The word for “good” was originally 良い (よい).

When it is written in Kanji, it is usually read as よい.

All the conjugations are still derived from よい and not いい.

The conjugation pattern is the same as the other い-Adjectives.

You can add です to make it polite.

The honorific polite form of いい and よい is よろしい.

⚠ No だ and だ's conjugations after い-Adjectives.

Both だ and い-Adjectives express a state of being, one following the other would be a redundancy and grammaticaly incorrect.

|

よい 村だ |

|---|---|

| This is a nice village. | |

|

それは 良かった |

| That's good to hear. | |

|

よくないらしい |

| It seems he's in bad shape. | |

か and も suffix

何か - Something

何 means what.If you add か, it becomes "something".

It also works with other questions words:

誰か: someone

いつか: sometime

どこか: somewhere

何か 持って 来ました。 I brought something.

私が 何か 嫌なことをしましたか。 Did I do something you didn't like?

何か 忘れてる Am I forgetting something?

|

何か 言えよ |

|---|---|

| Say something. | |

|

何か 来る |

| Something's coming! | |

|

何かお 探しか |

| Are you looking for something? | |

何も - Anything, nothing

何 means what.If you add も, it becomes "nothing" or "anything.

It also works with other questions words:

誰も: no one

どこも: somewhere

The verb must be in the negative form.

For いつも, the verb can be postive or negative.

いつも: anytime, always

何も 知らないジョン・スノー You know nothing John Snow.

ここには 何も 無い。 There's nothing here.

何も 言うことはない I have nothing to say.

|

あいや… 何も… |

|---|---|

| Oh, no, it was nothing. | |

|

何も 食べないの? |

| Aren't you going to eat? | |

|

本当に 何もないの? |

| Is there really nothing? | |

誰か - Someone

何 means what.If you add か, it becomes "something".

It also works with other questions words:

誰か: someone

いつか: sometime

どこか: somewhere

誰かいますか。 Is someone here ?

誰かが 壊した。 Someone broke it.

誰かがおいしいクッキーを 全部 食べた。 Someone ate all the delicious cookies.

|

誰か 来る! |

|---|---|

| Someone's coming! | |

|

誰かいるの? |

| Is someone there? | |

|

誰かいないの |

| Is anyone home?! | |

誰も - Anyone

何 means what.If you add も, it becomes "nothing" or "anything.

It also works with other questions words:

誰も: no one

どこも: somewhere

The verb must be in the negative form.

For いつも, the verb can be postive or negative.

いつも: anytime, always

誰も 見ていない。 Nobody is looking.

誰も 知らない。 No one knows.

誰もいない。 Nobody's here.

|

誰もいない |

|---|---|

| No one's here. | |

|

誰も いないね。 |

| Where is everybody? | |

|

誰もいませんか? |

| Hello. Is there anybody in there? | |

いつか - Sometime

何 means what.If you add か, it becomes "something".

It also works with other questions words:

誰か: someone

いつか: sometime

どこか: somewhere

いつかまた. Some other time.

未来のいつか。 At some point in the future.

私はいつか 子供を 産む。 I will have children someday.

|

でも いつか… |

|---|---|

| But someday... | |

|

いつか 必ず |

| One day, for sure. | |

|

いつか… 追いつくから |

| You'll catch up eventually. | |

いつも - Always; usually; habitually

何 means what.If you add も, it becomes "nothing" or "anything.

It also works with other questions words:

誰も: no one

どこも: somewhere

The verb must be in the negative form.

For いつも, the verb can be postive or negative.

いつも: anytime, always

いつも 眠い。 Always sleepy.

私はいつも 暇だ。 I'm always bored.

いつも 傍らにいる Always by your side

|

いつもの |

|---|---|

| I want my usual! | |

|

いつものことだな |

| Is a normal thing now.. | |

|

いつも あそこにあるの |

| It's always there. | |

どこか - Somewhere

何 means what.If you add か, it becomes "something".

It also works with other questions words:

誰か: someone

いつか: sometime

どこか: somewhere

どこかへ 行きましたか。 Did you go anywhere ?

どこかに 行きたい。 I want to go somewhere.

どこかの 国。 Some country.

|

どこかへ 行くの? |

|---|---|

| Where are you going? | |

|

また どこか 行くの? |

| We're going somewhere else? | |

|

でもこの 人どこかで… |

| But, I think I've seen her somewhere... | |

どこも - Nowhere

何 means what.If you add も, it becomes "nothing" or "anything.

It also works with other questions words:

誰も: no one

どこも: somewhere

The verb must be in the negative form.

For いつも, the verb can be postive or negative.

いつも: anytime, always

どこもよくないです。 None of the places are good.

どこも変なと 来ないよね? I don't look strange anywhere. right?!

どこへも行きませんでした。 I didn't go anywhere.

|

まだどこもお 休みだな |

|---|---|

| Looks like everything is closed, still. | |

|

どこも 痛くないかい? |

| Do you hurt anywhere? | |

Adverbs

Adjectives into adverbs

An adverb precedes the verb it modifies.You can turn adjectives into adverbs.

These adverbs are normally translated with "-ly" in english.

For い-Adjective, change the final い to く.

For な-Adjective, you add に.

No particles is attached to adverbs.

何かを 小さく 切る。 To cut something into small pieces.

わたしは 毎日 自分の 部屋で 一人 静かに 勉強します。 I study in my own room quietly every day.

簡単に 説明する。 To easily eplain.

|

レグー 早く 早く |

|---|---|

| Reg, hurry, come quick! | |

|

全然 全く 全然 |

| Absolutely not. Absolutely not at all. | |

|

皆さん お 静かに! |

| Everyone, quiet, please. | |

毎 (まい) - Every

毎 (まい) is a prefix that is directly attached to words or individual kanji (usually using their on-yomi reading),The resulting kanji compound is a noun/temporal adverb that means "each" or "every".

毎年ですか。 Is it every year?

毎日、 働きます。 I work everyday.

毎日、 忙しいです。 I am busy every day.

|

毎日毎日… |

|---|---|

| Day in and day out... | |

|

毎日 見る 夢 |

| The dream I see every day... | |

|

毎年こうなの? |

| Is it like this every year? | |

よく - Often

You can use frequency adverbs to describe how often you do something.No particles is attached to adverbs.

よく is the adverbial form of いい, so it can also mean "nicely" or "skillfully".

That's the most frequent use.

私は よく喫茶店に 行きます。 I often go to a coffee shop.

ここよく 来るの? Do you come here often?

妹はよく 笑います。 My little sister laughs a lot.

|

よく 喋るガキだ |

|---|---|

| You talk a lot, child. | |

|

よく 言われるよ |

| Yeah, I hear that a lot. | |

|

よくあることです |

| Happens all the time. | |

時々 (ときどき) - Sometimes

You can use frequency adverbs to describe how often you do something.No particles is attached to adverbs.

時 (とき) means time.

時々 (ときどき) means sometime.

私は 時々 喫茶店に 行きます。 I sometimes go to a coffee shop.

時々 背中が 痛い。 I have a pain in my back sometimes.

時々 タクシーに 乗ります。 I sometimes take a taxi.

|

時々 |

|---|---|

| Every now and then. | |

|

鹿も 時々ね |

| Sometimes deers. | |

|

時々ここに 来ていい? |

| Can I visit you once in a while? | |

全然 (ぜんぜん) - Never

You can use frequency adverbs to describe how often you do something.全然 (ぜんぜん) is an adverb that usually precedes verbs in their negative form (or adjectives with negative connotations, such as だめ) in order to express the nuance of "not at all" or "absolutely not".

Although 全然 is usually used in this fashion, it may also be used together with verbs in affirmative form in informal speech, or adjectives with positive connotations, In this case, it expresses the nuance of "very or extremely".

As with all adverbs in Japanese, the adverb precedes the verb/adjective it modifies.

いえ。 全然 。 Nope. Not at all.

私は 全然 テレビをみません。 I do not watch TV at all.

お 酒は 全然 飲みません。 I don't drink alcohol at all.

|

全然だよ |

|---|---|

| Not at all. | |

|

いや 全然 |

| No, no way! | |

|

全然 大丈夫 |

| It's fine, really. | |

もう - Already; anymore; again; other

もう is an adverb used to indicate and emphasize change of state or condition.Its translation is context dependent:

1) "already" or "now" in affirmative declarative sentences

2) "yet" or "already" in affirmative interrogative sentences

3) "(not) any more" or "(not) any longer" in negative sentences.

Like all Japanese adverbs, もう precedes the verb that it modifies.

It can also be used to express irritation.

もうだめだ。 It's no good anymore.

もう 夜です。 It's already nighttime.

もう 帰った。 They already went home.

|

もう 夏だね |

|---|---|

| It's already summer. | |

|

僕 もういいよ |

| I don't wanna play anymore. | |

|

ハハハハッ もう1 回 |

| Once again. | |

すぐ - At once

Adverb indicating short temporal or physical distance.もう すぐにね… Very soon.

はい すぐ 行きます Yes, I'll be down soon.

すぐ お 父さんに 手紙 書いて You need to write a letter to your father at once.

|

今すぐ? |

|---|---|

| Right now? | |

|

はい 今すぐ! |

| Right away... | |

|

もうすぐ 夏休みか |

| It's almost summer vacation. | |

ちょっと - A little

ちょっと means a little bit.It's often used to decline a proposal, in a soft indirect way, without directly voicing disapproval.

ちょっと 待って。 Wait a sec.

ちょっと、 君! Hey, you!

ちょっと 怖い。 I'm a little/quite scared.

|

ちょっと 待ってよ |

|---|---|

| Wait a second! | |

|

ちょっと 失礼 |

| Excuse me a minute. | |

|

ちょっと 外に 出てる |

| I'm going outside for a bit. | |

とても - Very; awfully; exceedingly

沖縄の海はとてもきれいでした。 The sea was very beautiful in Okinawa.今日はとても 暑いですね。 Today is very hot, isn't it?

1 月と 2月はとても 寒いです。 January and February are very cold.

|

とてもいい 子だった |

|---|---|

| She was a great girl. | |

|

とてもかわいい 赤ちゃん |

| It's such a cute baby. | |

|

とても 心の 優しい 人にね |

| And she's a very nice person, too. | |

たくさん - A lot

たくさん is used as an adverb modifying the amount or volume of something.いっぱい also means a lot. The two can usually be used interchangeably.

いっぱい sounds more a bit more colloquial than たくさん.

私は 京都でたくさん 写真を 撮りました。 I took many pictures in Kyoto.

野菜をたくさん 食べました。 I ate a lot of vegetables.

たくさんの 人たちがいた。 There were a lot of people.

|

たくさん 練習するの? |

|---|---|

| Do you practice a lot? | |

|

すごくたくさん 入ったわ |

| I got quite a bit in there. | |

|

わぁ~! たくさんあるね |

| Wow! There're so many! | |

くらい - Approximately; about

くらい is an adverbial particle used to roughly indicate amount or extent.It is usually translated as "about" or "approximately".

It always directly follows the amount/extent that it modifies.

くらい may be freely replaced by ぐらい without a change in meaning.

百 人くらい 集まりました。 About a hundred people gathered together.

この 靴はだいたい2 万 円くらいしました。 These shoes cost about 20.000 yen.

彼は10 歳くらいだろう。 He’s about 10 years old.

|

一週間に1 回くらい |

|---|---|

| About once a week. | |

|

20 回くらい |

| Probably around twenty. | |

|

15 分くらい 前 |

| About fifteen minutes ago. | |

あまり (ない) - (Not) very, (not) much~

あまり litteraly means "too much".When used in negative sentences, it means "not very (much)" instead.

It's usually used in negative sentences.

あんまり is a variant of あまり and usually used in conversation.

In limited situations, あまり can be used in affirmative sentences, too, In this case, it means 'very; too' with a negative implication.

あまり always precedes the verb.

たけしさんはあまり 勉強しません。 Takeshi does not study much.

この 本はあまりよくない。 This book is not very good.

あまり 調子がよくありません。 I don’t feel very well.

|

あまり 感心するなよ |

|---|---|

| Don't be so impressed. | |

|

あまり 高いものは 駄目だぞ |

| Nothing expensive. | |

|

いや あんまり |

| No, not really. | |

Numbers

Numbers 1-10

Numbers 1-10 for counters

Number + も

You can add も to a number when you want to say "as many as".Number + しか + Negative

You can add しか to the number and turn the predicate in the negative form whan you want to say "as few as" or "only".Counters

Counters

Japanese use different words when counting items.They are called counters.

The counter is placed after the number.

Here is a few counter eemples :

People: 一人 (nin) *Special eceptions are made for one person (一人, "hitori") and two people (二人, "futari")

(Small) objects: ー個 (ko)

Long thin objects (inc, bottles): ー本 (hon)

Thin, flat objects (inc, sheets of paper): ー枚 (mai)

Drinking glasses: ー杯 (hai)

Places: ー箇所 (kasho)

Seconds: 一秒(byou)

Minutes: 一分(fun)

Hours: 一時間(jikan)

Days: ー日 (nichi)

Weeks: 週間 (shuukan)

Months: ーヶ月 (kagetsu)

Years: ー年間 (nenkan)

Nights (spent overnight somewhere): ー泊 (haku)

Rolls of things (inc, scrolls): ー巻 (kan)

Pages: 一ページ (peeji)

Books: 一冊(satsu)

Letters: 一葉(you)

Homes: 一戸(ko)、一軒(ken)、一棟(mune)

Tatami mats: 一畳 (jou)

Tsubo (3.31 square meter area): ー坪 (tsubo)

Small animals (inc, most insects): 一匹 (hiki)

Large animals (and some insects): 一頭 (tou)

Birds (and rabbits): 一羽 (wa)

Fish: ー尾 (bi)

Chopsticks: 一膳 (zen)

Plates: 一皿 (sara)

Boats, ships: 一隻(seki)

Cars, trucks, etc.: 一台(dai)

Train cars: 一両(ryou)

Flowers: 一輪 (rin)

Beats (of music): 一拍(haku)

Stocks (e.g, on the stock market): 一株(kabu)

リーさんは 切手を三 枚 買いました。 Lee bought three stamps.

ビール二 本お 願いします。 2 bottles of beer please.

何 歳ですか。 How old are you?

Counting people

The counter for people is 人 (にん).One people and two people have irregular readings:

一人: ひとり

二人: ふたり

一人で 寂しい Alone and lonely.

うちは 四人 家族です。 There are four people in my family.

娘が 二人います。 I have two daughters.

Conjugation - Te form

Te form - Conjugation - The て-form is a very versatile conjugation in japanese.

A lot of grammar is

based on the て-form of verbs.

It can be used for:

- Making request

- Connecting activities

-

Giving / asking permission

- Interdictions

Te form - Adjectives Conjugation - You can conjugate adjectives to the て-form.

When two (or more)

adjectives are used to describe some thing or person, they can be combined into one sentence by changing the

first one to the て-Form.

い-Adjectives: change the い to くて

な-Adjectives: add で

柔らかくて

美味しいです。 It's tender and delicious.

あの 店のパスタは、 安くておいしい。 The pasta at that place is cheap and

delicious.

私の 部屋は、 狭くてきたない。 My room is small and messy.

|

堅くて 丈夫 |

|---|---|

| It's hard and sturdy. | |

|

優しくて 頼もしいもの |

| They're kind and reliable. | |

|

濃厚でおいしいです |

| It's so rich and delicious. | |

ている - Ongoing action or current state

The て-form can be joinded by the verb いる to form the ている conjugation.It means either :

- an action in progress

- a past event that is connected to the present.

In casual spoken Japanese the い is often dropped, (食べている → 食べてる)

The polite form is います, The auxiliary verb いる conjugates as る-verb.

When ~ていた, the past tense of ている, is used, it expresses an action that was progressing at certain time in the past or someone or something was keeping the action in the same state for a period of time in the past, and now that action is no longer in that state.

In casual spoken Japanese the い is often dropped, (言っていた → 言ってた)

何をしている? What are you doing?

寿司を 食べています。 I am eating sushi.

今、お 母さんが 病院で 寝ています。 My mother is sleeping in the hospital now.

|

寝ている |

|---|---|

| He's asleep. | |

|

開いている |

| It's open! | |

|

うわさは 聞いている |

| I've heard the rumors. | |

てある - Is / has been done (resulting state)

This is used when something is intentionally done and you can see the resulting state of that action.Therefore てある is only used with transitive verbs.

It is similar to using past tense form, but different in that it places emphasis on the action being done intentionally and the end result still being visible.

Take て-form of the verb and add ある.

このドアは 開けてある。 This door has been left open.

テレビ 台の 上に 置いてあるよ。 It has been placed on top of the TV stand. (something is on the TV stand)

明日の 準備をしてある。 I have done my preparation for tomorrow.

|

花が 供えてある |

|---|---|

| Someone left flowers. | |

|

作戦も 考えてある |

| I've thought up a plan, too. | |

|

奇麗に 洗ってあるから |

| I washed it well. | |

Connecting Sentences

Connecting て-form Verbs - Connecting activities

We can use the て-form to connect two activities in one sentence.You can express a string of action that happens one after another : "I did this and then I did that."

The first verb of the sentence is in the て-form, the tense of the second verb (or the last of the sentence) determines when these events take place.

Two verbs cannot be joined by the particle と, which only connects nouns.

今日は、六 時に 起きて 勉強しました。 Today I got up at six and studied.

夏 待つりに 行って 花火を 見ました。 We went to a summer festival and saw fireworks.

|

早く 帰って 読もう |

|---|---|

| I can't wait to get home and read this. | |

|

開けてみて |

| Open it and see. | |

|

黙って 聞け |

| Be quiet and listen. | |

くて / で - Connecting sentences

The same way you can connect two clauses with verbs, you can use the て-form for adjectives and nouns.It's used like the word "and".

For い-Adjectives, simply use their て-form.

For な-Adjectives and nouns, add で to connect clauses.

あの 店の 食べ物は 安くて、おいしいです。 The food at the restaurant is inexpensive and delicious.

オテルはきれいで、よかったです。 The hotel was clean and we were happy.

山下 先生は 日本人で、ご十 歳ぐらいいです。 Professor Yamashita is a Japanese and he is about fifty years old.

|

堅くて 丈夫 |

|---|---|

| It's hard and sturdy. | |

|

優しくて 頼もしいもの |

| They're kind and reliable. | |

|

濃厚でおいしいです |

| It's so rich and delicious. | |

ないで - Without doing~ ; to do without doing

This means that you don't do one thing while doing something else.Use the negative form of the verb (ない) and add で.

If no action follows ないで, it turns into a request (next lesson).

休まないで 仕事をする Work without taking a break.

何も 言わないで、 出て 行った。 Without saying a word. he left.

昨日 朝ご飯を 食べないで 学校へ 行きました。 I went to school yesterday without eating her breakfast.

|

すげー 見てないで 続けて |

|---|---|

| Amazing... Don't look. Just carry on! | |

|

俺だと 確認しないで 攻撃したのか? |

| In other words, you attacked without being entirely sure it was me? | |

|

ノックもしないで 入り込んで― |

| You come in here without even knocking? | |

Request

てください - Please do

ください is an auxiliary verb which indicates a polite request.To make a request, use the て-form of the verb and add ください.

ください is the imperative form of the verb くださる (the honorific version of くれる).

It's a rather direct way to ask someone to do something, when you are in a position of authority.

You can make a request more polite by using 〜てもらえませんか or 〜ていただけませんか.

Usually it's written in kana, but the kanji form for ください is 下さい.

食べてください。 Please eat.

やめてください。 Please stop.

この 本を 読んでください。 Please read this book.

|

聞いてください |

|---|---|

| Listen to this! | |

|

待ってください。 |

| Please wait a second. | |

|

ギター 教えてください |

| Please teach me how to play guitar. | |

ないでください - Please don't do

To request that someone refrain from doing something, use the negative short form of a verb and でください.ここで写真を撮らないでください。 Please don't take pictures.

行かないでください。 Please. don't go.

それを 食べないでください。 Please don’t eat that.

|

聞かないでください |

|---|---|

| Please don't ask. | |

|

笑わないでくださいね |

| Promise you won't laugh, okay? | |

|

気にしないでください |

| Please don't worry about it. | |

Permissison

てもいい - Give permission

To give permission to someone to do something, you can use the て form of the verb and add もいい.いい is the adjective for good.

It means that doing is okay.

You can add です after いい to be more polite.

In casual speech, you can drop the も.

高くてもいいです。 It is all right if it's expensive.

これを 見てもいい? Is it alright if I look at this?

|

弟子にしてもいいよ! |

|---|---|

| Sure, I'll make you my apprentice! | |

|

じゃあ からかってもいいんだね |

| I can tease you, then. | |

|

宿題 写してもいいよ |

| You can copy my answers. | |

てもいいですか - Ask permission

てもいいですか is a simple and casual way to ask permission to do something.In casual from, you can drop も and just use ていい with a rising intonation to indicate a question.

ここで 煙草を 吸ってもいいですか。 May I smoke here?

ビールでもいいですか。 Will beer do?

食べてもいいだろう。 It is okay if I eat. right?

|

見てもいい? |

|---|---|

| Can I look? | |

|

食べてもいいか |

| Can I eat it? | |

|

座ってもいいか? |

| Mind if I sit here? | |

なくてもいい - No permission needed

なくてもいい is used to tell someone that they don't have to do something, it's not necessary.なくて is the negative て-form.

Can be shortened to なくたっていい when spoken or even なくていい.

なくてもかまわない is a similar Expression.

It uses the word かまわない, meaning "don't care" or "don't mind".

学校に 行かなくてもいい。 I don't need to go to school.

好きじゃないなら、 食べなくてもいいですよ。 If you don't like it, you don't need to eat it.

来なくてもいいですよ。 You don't need to come.

|

別に 飛ばなくてもいいよ |

|---|---|

| You don't really need to fly. | |

|

そんなことは 気にしなくてもいい |

| You don't need to worry about that. | |

|

勝たなくてもいいよ |

| We don't need to win... | |

Interdiction

てはいけない - Interdiction, must not do

This form can be used as a strong way of saying something is prohibited.This phrase is referring to the acceptability of the action and not the possibility of the the action being executed.

This is used when someone is talking about set rules and regulations.

You can think of it as "must not" and "not allowed".

いけない is a more casual form of いけません.

てはならない also expresses prohibition and is a little stronger than はいけない.

In a conversation, ては is sometimes shortened to ちゃ, So, you can say ~ちゃいけません in a daily conversation to tell the listener not to do something.

Also, as a casual variation, there is てはだめだ.

この 部屋に 入ってはいけません。 You must not enter this room.

仕事に 休んではいけない。 You must not take time off from work.

ここから、 始まってはいけない。 You must not start from here.

|

決して 手を 出してはいけないよ |

|---|---|

| Don't touch it. Do you understand? | |

|

目を 合わせてはいけない |

| Number one: Don't make eye contact. | |

|

お 腹 壊してはいけないからな |

| We don't want to upset her stomach. | |

な - Don't

The stem form of a verb and な is an extremely strong imperative.It tends to be used mostly by males in very informal speech, or by a superior to a subordinate.

行くな。 Don't go!

話をするな! Don't talk !

お酒をのんだら運転するな! Don't drive after you drink!

|

来るな! |

|---|---|

| Stay back! | |

|

死ぬな! |

| Don't die! | |

|

さわるな さわるな! |

| Don't touch it, don't touch it! | |

Obligation

なければいけない - You must

When you say you must or need to do something.This shows some kind of duty or responsability.

なければ means if not.

いけない means not good or wrong.

From polite to casual:

ければなりません (polite)

ければいけません (polite)

ければいけない (casual)

ければならない (casual)

きゃだめだ (rude)

きゃ (rude)

仕事に 行かなければいけない。 I have to go to work.

覚えにくいけど、 覚えなければいけません。 It's difficult to remember. but I must.

彼に 会いたくないけど、 会わなければいけません。 I don't want to see him. but I must.

なければならない - Have to, need to, must, should

The phrase, taken as a whole, is used to indicate necessity, or make an assertion that something is expected to exist in a certain state.It is therefore equivalent to the English phrases "have to", "should" or "must".

なければ means if not.

ならない is the negative form of なる.

8 時に 駅まで 彼女を 迎えにいかなければならない。 I have to be at the station to pick her up by 8 o'clock.

髪の毛が長いから、切らなければならない。 My hair is long, so I have to cut it.

母を 手伝わなければならない。 I have to help my mom.

ないといけない - Must do; have an obligation to do

The phrase "といけない" means that it is not acceptable or permitted to do something, and in this structure it is preceded by the negative of a verb.Therefore, it is not acceptable or permitted not to something; hence, the action must be or has to be carried out.

This double negative structure results in a pattern roughly equivalent to the English "have to" or "must do" something.

This can also be conjugated and used as:

- ないといけません (naito ikemasen) more formal.

- ないとダメです (naito dame desu) alternate version.

- ないと (naito) short version.

そろそろ 寝ないといけない。 I have to sleep soon.

私は 家に 帰らないといけない。 I have to go home.

今から 勉強をしないといけない。 I have to study now.

|

2 個 買わないといけないの? |

|---|---|

| So you have to buy two decks? | |

|

実践もしておかないといけないよ |

| but you need to gain experience, too. | |

|

どうして 毎日 働かないといけないの? |

| Why do I have to work every day? | |

なくちゃいけない - Must do; need to; gotta do

You use なければいけない to say it's necessary to do something if not … or otherwise ...なければ means if not.

いけない means not good or wrong.

The casual form often used when speaking is なきゃいけない.

Likewise, なくちゃ means "unless"

日本語を 勉強しなくちゃいけない。 You must study Japanese.

もっと 文法を 勉強しなくちゃいけない。 I must study more grammar.

食べなくちゃダメ。 Must eat !

|

助け合って 生きていかなくちゃいけないの |

|---|---|

| We have to support each other. | |

|

自分のことは 自分でしなくちゃいけないから |

| You have to do everything on your own. | |

|

くそっ 天才の 証明をしなくちゃいけないのに |

| Damn, I have to prove that I'm a genius. | |

なくてはいけない - Must do; need to do

Meaning: must do; need to do.急がなくてはいけない。 I have to hurry.

寝なくてはいけない。 I must go to sleep.

日本語をもっと 勉強しなくてはいけない。 I really need to study Japanese more.

|

誰かが… 誰かがやらなくてはいけないんだ |

|---|---|

| Someone... Someone has to do it! | |

|

もう ここから いなくならなくてはいけない |

| I can't stay here any longer. | |

|

しなくてはいけないことが… |

| There's something I have to do. | |

なくてはならない - Must do; need to do

Meaning: must do; need to do.もう 行かなくてはならない。 I must go now.

毎日 勉強をしなくてはならない。 You must study every day.

君が 決めなくてはならないよ。 You have to decide.

|

会社に 戻らなくてはならないので |

|---|---|

| I must get back to the office. | |

|

倒さなくてはならないんだ |

| He must be defeated! | |

|

自分を 抑え 冷静でなくてはならない |

| A coach need to be in control of himself and calm. | |

Like and dislike

好き - To like

好き (すき) means like.In japanese, "To like" is an adjective (a な Adjective) and not a verb.

You can think of it as "desirable".

It usually works with が that indicates the object of the adjective.

私はステーキが 好きです。 I like steak.

サッちゃん、 好きだよ。 Satchan. I like you.

好き? Do you like (it)?

|

好きです |

|---|---|

| I like you. | |

|

私も 好き |

| I like them, too! | |

|

好きじゃないよ |

| No, I don't. | |

のが好き - To like doing

好き (すき) means like and is a な-Adjective.Add の after the short form of a verb to express the idea of "doing ".

So: Verb + のが + 好き means to like doing .

私は 本を 読むのが 好き。 I like reading books.

私はサッカーをするのが 好き。 I like playing soccer.

私は 文法の 勉強をするのが 好き。 I like studying grammar. (grammar study)

|

どんなのが 好きなんだろう |

|---|---|

| I wonder what type he likes. | |

|

カワイイものが 好き かな |

| Oh, I like cute things. | |

|

そういうのが 好きなんだよ 俺は |

| Now, this is the kind of stuff I like. | |

嫌い (きらい) - To dislike

You use 好き to say you like something or like doing something,嫌い (きらい) works the same way to say "don't like".

Although it ends with い, it's a な-adjective, just like 好き.

マンガが 嫌い。 I don't like manga.

マンガを 読むのが 嫌い。 I don't like cleaning my room.

パイナップルが 嫌い? Do you dislike pineapple?

|

雨は 嫌いだ |

|---|---|

| Ahh, I hate the rain. | |

|

あー 大嫌いだ! |

| I hate you so much! | |

|

人間はキライ |

| I hate humans! | |

To be good / bad at

のが上手 (のがじょうず) - To be good at

上手 (じょうず) is a な-Adjective that means skillful, or good at.Add の after the short form of a verb to express the idea of "doing ".

Connect the two with が to mean someone is good at doing something (or just good at).

In casual form, only 上手 is used and it's much more frequent.

When talking about yourself you can use the な-adjective とくい instead of 上手.

トムは 料理を 作るのが 上手です。 Tom is good at cooking meals.

上田 先生はテニスがお 上手です。 Professor Ueda is good at tennis.

私は 文法を 勉強するのが 得意です。 I’m good at studying grammar.

|

上手だ。 |

|---|---|

| Very nice. | |

|

踊りが 上手なのね |

| He's a good dancer. | |

|

ボートこぐの 上手なのね |

| You're very good at rowing. | |

のが下手 (のがへた) - To be bad at doing

下手 (へた) is a な-Adjective that means unskillful, or bad at.Add の after the short form of a verb to express the idea of "doing ".

Connect the two with が to mean someone is bad at doing something (or just bad at).

In casual form, only 下手 is used and it's much more frequent.

When talking about yourself you can use the な-adjective 苦手 (にがて) instead of 下手.

たけしあさんは 英語を 話すのが 下手です。 Takeshi is not a good speaker of japanese.

私は 日本語を 話すのが 苦手です。 I'm not good at speaking japanese.

彼はお 箸を 使うのがへただ。 He is bad at using chopsticks.

|

表現するのが 下手? |

|---|---|

| You're not good at expressing yourself? | |

|

嘘が 下手ね |

| You're terrible at telling lies. | |

|

もしかして 私の 掃除 下手? |

| Am I doing a crappy job of cleaning? | |

詳しい - Knowledgeable

詳しい (くわし) is an い-adjective meaning detailed, accurate or well-acquainted.You can use it with に to say someone knows a lot about something.

たけしはカメラに 詳しいい。 Takeshi knows a lot about cameras.

彼は 地理に 詳しいの。 He's knows a lot about geography.

彼はコンピューターに 詳しい。 He is very familiar with computer.

|

詳しい 人は? |

|---|---|

| Do you know anyone who might? | |

|

高校生が 詳しいのね |

| You know a lot for a high school kid. | |

|

へえ 詳しいな |

| I didn't expect you to know that. | |

Conjunction

そして - And; and then; thus; and now~

This is used to express supplemental information.それで: "and therefore", to introduce the consequence of what comes before it

そして: "and last but not least", to say something remarkable

それから: "and then", to add an item that comes later in time or in order of the importance

そして 行ってしまった。 And then (he) was gone.

そして 私はあなたに 出会った。 And then I met you.

そして、 私は 朝ごはんを 食べました。 And then, I ate breakfast.

|

そして もう 1つ |

|---|---|

| And there is one more. | |

|

そして 死神が 来た… |

| And now the Shinigami's here. | |

|

そして 俺は 孤立した |

| And then… I found myself all alone. | |

それから - And; and then; after that; since then

This is used to express supplemental information.それで: "and therefore", to introduce the consequence of what comes before it

そして: "and last but not least", to say something remarkable

それから: "and then", to add an item that comes later in time or in order of the importance

それから、 私は 昼ごはんを 食べました。 And then, I ate lunch.

あなたはそれからどうするのですか。 What will you do after that?

それから、 私たちはアイスを 食べました。 And then, we ate ice cream.

|

それから どうしたの |

|---|---|

| So what happened after that? | |

|

それから 彼女はエリカ |

| And this is Erica. | |

|

いや いいけど それから |

| No, not really. Go on. | |

それで - And therefore

This is used to express supplemental information.それで: "and therefore", to introduce the consequence of what comes before it

そして: "and last but not least", to say something remarkable